Last issue, in the first in this two-part series on trauma and coaching, Ty Francis explored organisational trauma.

In part two, Anne Roques explores dealing with individual trauma in the workplace as a coach and supervisor

Drawing on my 20 plus years’ experience as a coach and supervisor, I share in this article some useful tips on how to recognise symptoms of trauma and accompany clients and coaches who are dealing with the effects of trauma.

As professional coaches, we’re rarely trained to diagnose and treat trauma in the workplace. Traumatogenic events, however, are common in the corporate environment and may heavily impact the issue of our intervention.

Exploring terms

We employ the term traumatogenic, as reactions to dire events and resilience depend on individual resources. Therefore the same event may not necessarily be considered traumatic for some people, and may have different impacts on different people.

We need to distinguish ‘shock trauma’, which designates a recent traumatic event occurring in the workplace or outside (such as a natural disaster or a terrorist attack), from ‘developmental trauma’, which is related to childhood experiences or collective events that will not be explored in this article.

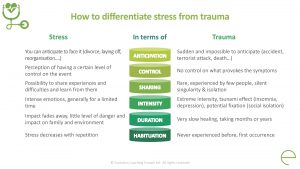

Most of our executive clients face extremely demanding situations and are frequently exposed to stress triggers. That doesn’t mean they suffer from trauma, as stressful events can be anticipated, controlled and, in many occurrences, dealt with and shared with other people. On the contrary, traumatic events are unique in their nature and intensity, as well as in terms of healing time (see Figure 1).

Although stressful events may also be sudden and intense, their impact tends to fade away with time, and decrease with habituation. Traumatic events, however, are so intense and so singular, that they tend to remain vivid and difficult to overcome without a specific intervention.

Post-traumatic symptoms are numerous and can span from aggressive behaviour to avoidance and distress. Some clients may experience sleeping problems and recurring nightmares. Others might rehash memories of the traumatic situation, without being able to integrate the event and move on.

Coaching

Our coaching stance is the key to bringing back the traumatised human being and just be there, resonating with them in a ‘circle of intimacy’ where our client can feel safe enough to rest and share their experience.

Guiding the client through the integration process requires all our ability to be empathic and steady, patient and yet a little directive. We also need to be very aware of the risk of re-traumatisation, and make sure our clients are ready to revisit their traumatic events in order to work through them.

Integrating a trauma impacts three different levels:

– On a cognitive level, we need to help the client recover their ability to think normally and stay rational. Eye contact and guided breathing techniques can be useful here.

– On an emotional level, the client will need to be able to feel and handle their emotions in a balanced way, as the post-traumatic state is often associated with overwhelming emotions or total numbness.

– Finally, they will need to be able to recollect the traumatic events in a regulated way, suitable to the situation and the environment.

Typical symptoms indicating your client hasn’t integrated a traumatic episode include when they’re unable to relate the painful events in a logical manner, or when their narrative is repetitive and lacking distance or conciseness.

The process

My practice is inspired by Salutogenesis (the study of the origins of health), which focuses on factors that support health and wellbeing, rather than on factors that cause disease, and which relies on coherence as the key to overcoming hardship. The coaching intervention consists in guiding the client to control, understand and, eventually, give meaning to what happened, in order to consider or be able to move on and face the future.

The control phase consists in guiding the client to breathe deeply and connect with their body sensations, while asking them to relate the facts in detail. I help them build a factual, detailed narrative of what happened, making sure they do so in the past tense. Specifically, I make sure they identify the worst moment of all, before labelling it as ‘that was then!’, to remind them the traumatic experience is over.

Then we move on to analysing the facts, to understand the link that can be made with personal thoughts and values. Failing to identify or recognise the impact on personal values often delays or prevents healing, causing the client to be stuck in their recovery process.

I ask precise questions to invite the client to connect with their body sensations, focusing on the ‘felt sense’ to leverage resources other than the cognitive brain. The intention is to teach them to listen to their body, because I’m convinced the body keeps traces of our experiences and is incapable of lying (eg, Van der Kolk, 2014).

In this phase, clients often struggle with finding appropriate terms to define their feelings, and it might be useful to provide them with the correct definitions and differences between emotion, feeling, sentiment, mood,

and perception.

An emotional dictionary, like Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions, can be handy. Linking the experience to personal values and body feelings provides a different reading of the events and creates a new neuronal pathway in the brain, replacing the automatic reaction activated (and sometimes over-activated) by the negative event.

The third and last part of the intervention consists in helping the client practise self-care and build resilience, mobilising new resources to store events in the past.

This phase will show the client how to manage their reactions through deep breathing, and how to practise self-care to recharge their emotional batteries.

At this stage, the client should be ready to identify a symbolic ritual to put the traumatic event in the past. This doesn’t mean forgetting or erasing what happened, but simply moving on by turning a symbolic page and getting ready to look ahead.

Post-traumatic growth happens when individuals, having successfully integrated traumatic events, feel stronger and yet more aware of their vulnerability. They generally also declare having reconsidered their life priorities and feeling a stronger sense of closeness and compassion.

Coaches and supervisors needn’t be afraid of the baggage that clients bring from their backstories. As long as we work with good attunement and trust our coaching skills, we can ground ourselves in our healthy autonomy, helping our clients to do the same. This requires that we recognise our own limits as coaches and supervisors and seek help if necessary.

I have so much more to say and share as this is such a vast subject and my personal curiosity is unstoppable, but I’d like to end this article with an invitation to reflect on the following:

- How comfortable are you with recognising traumatogenic symptoms in your clients?

- How do you decide whether you can explore the subject of work-related trauma with your client?

- What boundaries do you set between our field and psychotherapy?

- Are you clear on the thread between personal trauma and workplace trauma?

- If not, what resources could you find to build your own tool box to recognise and address these matters?

CASE STUDY 1: JOAN

Names and situations have been modified to ensure confidentiality

Joan is a vice president of sales in the IT industry. In the last four years she has received three Best Sales Results awards and yet she is to be made redundant in a few days, for the third time. Each time she’s been made redundant in a very sudden and shocking way.

The first time the cause was her aggressive behaviour within the organisation. Being so driven on achieving her objectives, she had put too much pressure on her internal partners.

She obtained a good compensation package and bounced back very quickly, joining an IT start-up with a result-driven culture. However, faced with reckless and inhumane senior management, she got very stressed, started losing her self-confidence, and her results plummeted. She got fired after a mere nine months, but the emotional pain seemed compensated by a good financial package negotiated by her lawyer.

During the coaching, we worked on acknowledging her felt sense and bruised feelings, understanding the values that had been violated, her strengths and motivation levers. The idea was to learn from these two painful experiences and be more aware of her strengths and pitfalls.

She obtained a senior VP position within a very human and balanced team, selling an IT service that was very much aligned with her beliefs and values. All was perfect until the US senior management decided to shut down the European activities within a week. Her shock was so intense that she said she felt like a dog abandoned by its owner.

Her body went into shutdown, and she felt like avoiding anything related to the corporate world. Although she had lost all her motivation, she was compelled to go back on the treadmill due to heavy financial commitments.

The working phases of her coaching were the following:

- Identifying the worst moment (receiving the announcement email on the evening of her daughter’s birthday)

- Collecting all the facts and events to build an orderly narrative, naming and accepting all the painful feelings

- Finding a symbolic ritual to put things in the past (she decided to make a collage of her story and then burn it)

After this process, she felt ready to look ahead. She found a new job within two months.

CASE STUDY 1: MANUEL

Names and situations have been modified to ensure confidentiality

Manuel holds a European role in a major international finance institution, managing a team of 10 people dedicated to the development and maintenance of the internal application supporting the decision process of the investment bankers.

After several successful years, his functional boss announced via video call that the application was going to be stopped and replaced in six months’ time.

The coaching started because Manuel seemed to have gone into ‘freeze’ mode and no one, himself included, can explain his sudden lack of involvement and motivation.

During the coaching, I invited him to make meaning of the events, and identify the values that were trampled upon.

Although Manuel understood the organisational rationale for this decision, he didn’t seem to be able to overcome the event and deal with his persisting emotions. He could name his sadness and his fear of losing his job, but his emotions were far too intense considering the actual situation.

Following my intuition, I questioned him further and found out that he was also coping with the sudden death of his mother, which occurred within the same month of his work-related event.

Through evoking the worst moment of the past and working on the link between emotions and values, he managed to ‘archive’ all these events in the past and gently recover. This allowed him to face the reality and find the necessary motivation to work on the transition between the old application and the new digital tool.

He is now very proud to have gone through all this and very much looking forward to his next career steps.

Figure 1: Stress vs trauma

- B Van der Kolk, The body keeps the score: Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. Penguin UK, 2014

- Gisela Perren Klingler, founder of the Institute of Psycho-Trauma in Switzerland: Emergency Psycho-social Support

- P A Levine, Waking the Tiger: healing trauma. North Atlantic Books, 1997

- M Raber, P Linden, A Vilvovskya and D Treleaven, Panel Discussion: Trauma and the Body: Trauma awareness fundamentals for embodied professionals

- G Mate, When the Body Says No: The cost of hidden stress, Vintage Canada, 2011

- J Vaughan Smith, Coaching and Trauma: From surviving to thriving: Moving beyond the survival self. Open University Press, 2019

- Susannah and Ya’Acov Darling Khan, founders of movement medicine: www.schoolofmovementmedicine.com/about-school-of-movement-medicine/the-schools-story/

- David Grove, founder of Clean Language

- J Lawley and P Tompkins, Metaphors in Mind: Transforming through symbolic modelling. Developing Company Press, 2000

- www.cleanlearning.co.uk

- Somatic Coaching:

- www.embodimentunlimited.com

- www.strozzinstitute.com

About the author

- Anne Roques is an experienced leadership coach, guiding transformation, especially in chaotic situations. She works mostly with blue-chip companies and their leaders and has been an accredited supervisor with CSA since 2009.

Her corporate career was as a finance director and then supply chain executive with chemical companies, with a broad track record of organisational challenges, from strategy design to execution. She is Franco-British and lives as a global citizen. - www.evolution-coaching.org

- www.anneroques.com