How do you decide what to charge your client, ask Clare Norman and Michelle Lucas in this series on fees in coaching and coaching supervision. Part 2: pitching your fees

Whether you’re starting out or have been coaching for some time, a common conundrum is how to pitch your fees.

Our last article explored the disparity between supervision and coaching rates (https://bit.ly/32gAIEp). This time, we focus purely on coaching where, just like supervision, there’s a lack of transparency among practitioners. An example of this occurred recently when one of a group of coaches commented on the double-bind we find ourselves in, explaining: “I don’t want to talk about fees – it’s a no-win situation; either I’ll feel rubbish because I can’t command what other people can or I’ll feel guilty that I’m earning more than is appropriate.”

But if we don’t talk about our fees, we’re left with not knowing – and the opaqueness continues. So how can we start to open up the conversation? Let’s start by reviewing what (anonymous) research there is already out there about the price of coaching.

Some research was carried out by the Association for Coaching (AC) in 2004 (yes, 2004: that was the most recent we could find!). It reported that the average coaching rate when taken on a per individual session basis was £50 to £75 per hour, rising to more than £100 per session per hour when part of a package or monthly rate, and to an average of £125 to £250 per hour when offered in a business context, again as part of a programme of coaching, or monthly fee. To bring this up to date, we looked at the Life Coach Directory, where coaches are selling directly to individuals, and it seems that, for individual coaching in 2020, rates have not changed much, ranging from £55 to £90 per hour.

More recent figures are available via the 6th Ridler Report (2016), where organisations were asked about the fees they pay to external coaches per hour at different levels of the organisation. The greatest variability in fee rates is at group CEO/main board level. Some 40% were above £1,000 per hour, and 28% were at £500 per hour, but the range spanned from £300 to £2,000 per hour. The highest rates here tend to be paid to people more akin to business mentors than coaches. At senior executive level, 21% of fees are at or above £1,000 per hour. For senior managers, 75% of fees are at or less than £500. For middle managers, 91% are at or less than £500.

In 2017, Henley Business School, in partnership with the European Mentoring & Coaching Council, published a study (carried out in 2016), separating coaching funded by corporates or individuals. Again, the range was wide, with 54% of participants charging between €101 and €399 per hour for corporate funded coaches and, when individually funded, 57% of coaches charged less than €101 per hour and 40% charged between €101 and €199 per hour, with only 3% charging more than this.

The four-figure hourly sums quoted in the Ridler Report are referred to by some coach training organisations and marketeers who want to position coaching as a lucrative enterprise, to sell their own wares off the back of that tempting earning potential. However, in our experience, these rates are the exception rather than the norm.

Nonetheless, even where there’s less variability, the rates for senior executives and senior managers exceed those identified by the AC for rates in a business context. So perhaps rates have risen, or perhaps we’re comparing ‘apples with pears’. The Ridler Report findings are focused only on organisational fees.

We’ve noticed that often, large organisations don’t engage directly with independent practitioners, rather they engage a consultancy as an intermediary, managing quality control and financial administration. The supposed ‘hourly’ fee may be masking the mark-up that the third party charges for its own cost to serve. In our experience the hourly rate the practitioner receives may be as little as a third of what the organisation pays. Additionally, the report doesn’t give us the full picture of the spectrum across industries (and we know from our own practices that what we can charge will differ depending on the nature of the sector we work in). Finally, the report didn’t consider coaching that was being funded by an individual.

The AC found that “coaches will typically consider a number of questions before they determine their rate. The most popular explanation is based on personal calculations which considers personal factors such as ‘how much am I worth?’, ‘what experience do I have?’, ‘what training have I invested in?’, ‘how much do I require in order to make a living?’ and ‘what contribution do I need to make to my income?’

Others based their explanation on perceived attractiveness to the market by considering ‘what is an affordable rate?’, ‘what will be considered competitive?’, and ‘what represents good value for money?’

The previous two explanations are often informed by coaches’ market research, which also forms a separate category, and is the third key explanation. Questions coaches explore include ‘what is the market charging (in my area)?’ and ‘what are my peers charging?’ ”

We notice that several variables underlie these questions:

- Coach – is the coach a novice or a master or somewhere between? All the professional coaching bodies differentiate their members by number of hours of experience (among other criteria). This might lead us to a sliding scale of rates as a coach accumulates more hours.

- Client – is the client private or from an organisation? That may be further complicated by the sector of an organisation: are they a not-for-profit or a financial services organisation or somewhere between?

- Subject matter – is the coaching helping an individual to work through redundancy, about wellbeing and stress management, or about getting a candidate promotion ready, each of which might require a different pricing model?

- Coaching organisation – is the coach selling directly or through an associateship?

- Programme and session variables – is this a one-off or a package of coaching where we might discount for volume? How long is a session?

- Location – are there city vs regional rates? Are there any on-costs to deliver the work, for example travel expenses or time involved or infrastructure costs for working virtually?

- Market or contextual – some client groups will benefit from coaching irrespective of their ability to pay. Some coaching consultancies (not just charities and voluntary organisations) offer pro-bono services. This can affect what commercial organisations can command with similar client groups.

- Portfolio mix – coaches may decide to add a premium to their paid services to cover the cost of pro-bono coaching.

- Employment – what kind of salary could the coach command as an employee based on skills and experience? What is the hourly rate for? For example: How do coaches account for holiday pay, sick pay, business development costs, business administration costs?

So far, so complex. Many, but not all, coaches are self-employed. So perhaps we could take a more bottom-up approach. What if we looked at how much we might earn as an hourly rate if we were employed, as though we were a senior leader where coaching is part of our role. If we had a salary comparison, we could work out an hourly rate.

Or could we? Our employment contract includes paid holidays, sick pay, compassionate leave, a pension, continuous professional development and coaching supervision – so much more than an hourly rate. Looking at that whole package (versus salary alone), we might be looking at, say, an uplift of 30% on our basic salary. We also need to consider that we have no non-earning time in paid employment. It doesn’t matter whether we are networking, managing others or writing a business plan – we are paid.

Conversely as an independent coach, the hours of administration, business development, design work and preparation are all non-fee-earning. Many full-time coaches work on the basis of three out of five days being client-facing, with one day for admin and one for business development. This means that our daily rate needs to be 1.6 (or 5/3) of our employed rate to cover these non-fee earning days. Even that doesn’t take account of those three days not being eight full hours of coaching as our energy levels wouldn’t support that.

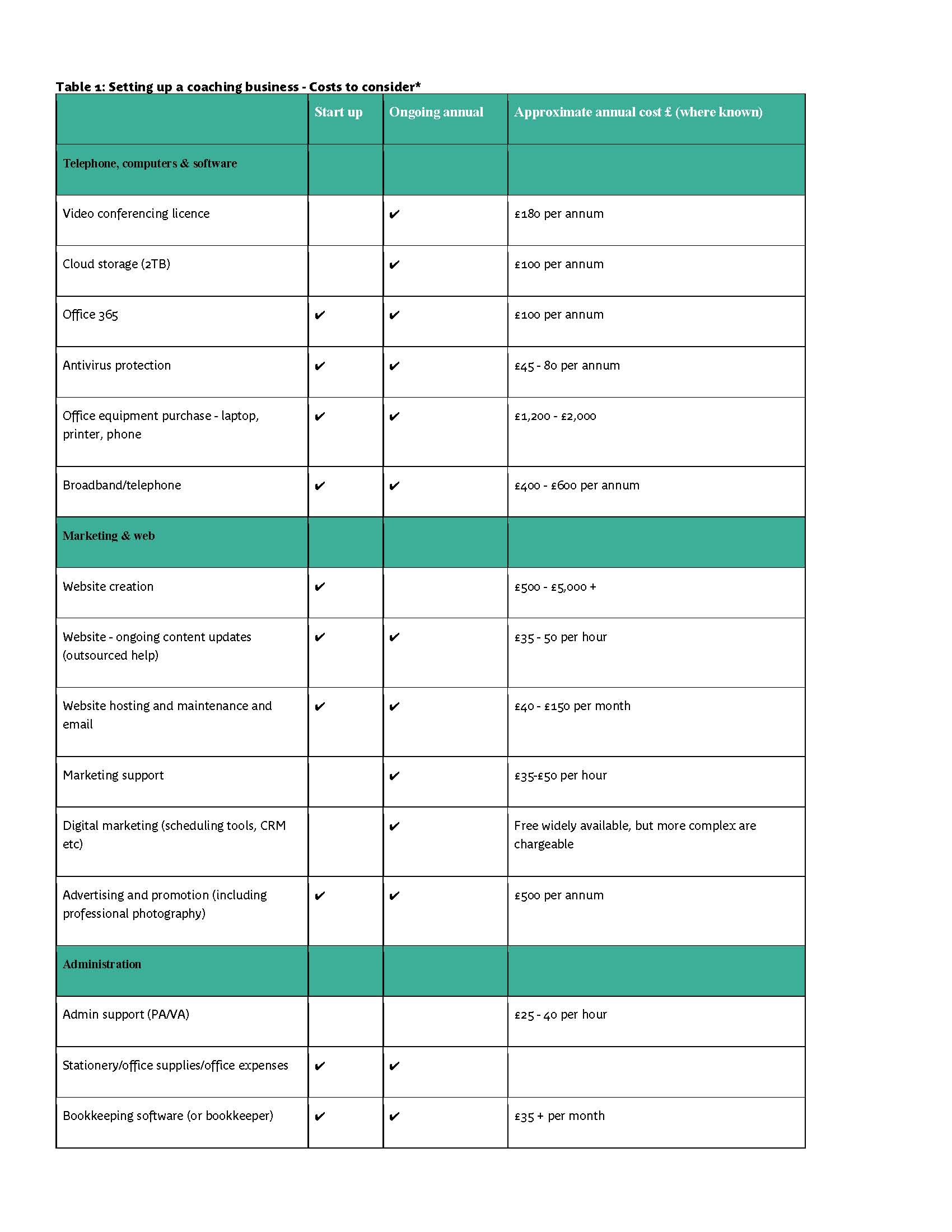

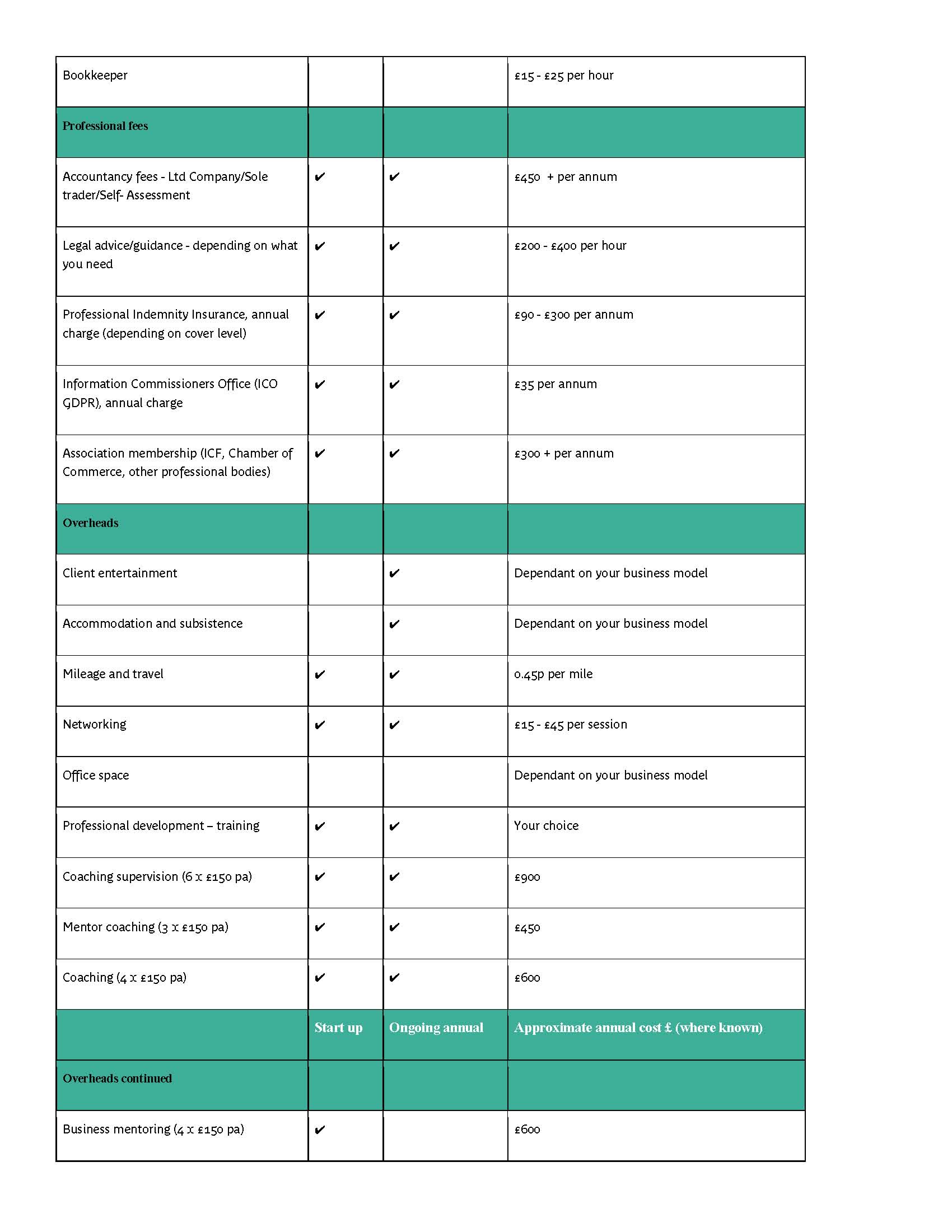

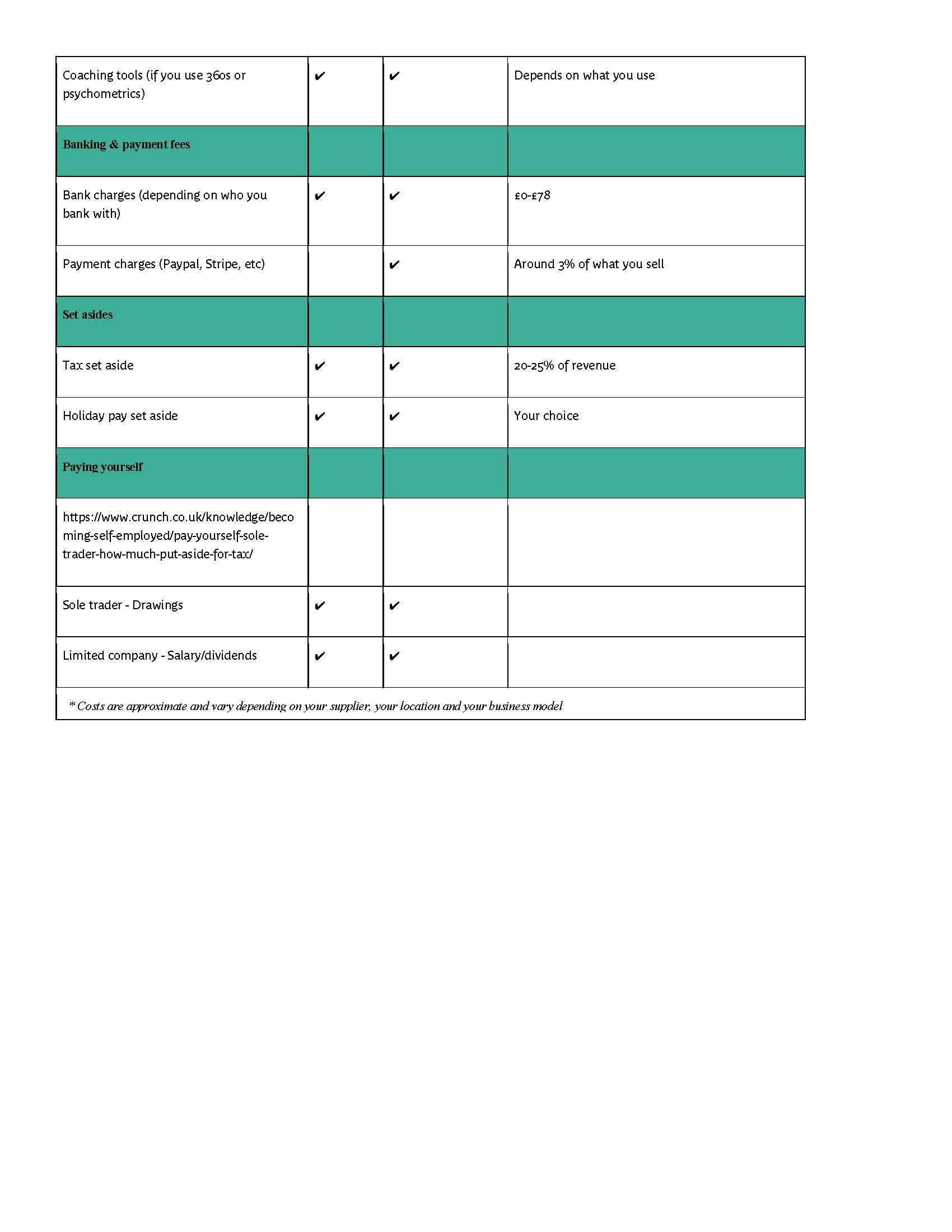

Additionally, there are significant costs to serve – part of any business overheads. Many employees won’t see this as a personal benefit, but for self-employed coaches it’s very much a personal cost. Despite the coach being the core asset of their business, ongoing professional costs can be substantial (see Table 1) and let’s not forget our original expenditure to train as a professional coach which might be anything from £2,500 to £10,000.

If we are going to calculate a market rate comparison, we need to consider:

S = market salary (basic pay)

B = additional benefits (eg, pension, paid holiday, bonus)

W = days available for work

I = set up costs

C = ongoing costs

Perhaps a formula:

Daily Fee =

(S +B+I +C)

W

This might give us a daily rate, from which we might expect to work with 2-3 clients; each session being 90-120 minutes duration (though we realise many coaches offer shorter sessions) with time in between to refresh, restore. So to get to a sessional fee we would divide the daily fee by, say 2.5.

Alternatively, we could look at this from the other end of the telescope by examining the return on investment (ROI) that our clients are likely to gain. Price according to value rather than cost if you like. ROI studies for coaching are usually carried out in an organisational context, so this may not apply for private coaching. But if we look at those studies, we see something like this:

- Coaching greatly accelerates the rate at which an individual learns and contributes from their learning. Studies have shown training alone changes behaviour by 20% and training followed by coaching changes behaviour by 88% (Olivero, Bane & Kopelman, 1997)

- “Coaching has a 2x greater impact on business results (productivity, engagement, etc.) vs. paying for performance” (Bersin & Associates, 2011)

- Coaching gives a conservative $100,000 financial benefit, with 28% of respondents indicating over $500,000 (Lore Research, 2002)

- “The vast majority (86%) of those able to provide figures to calculate company ROI indicated that their company had at least made their investment back. In fact, almost one fifth (19%) indicated an ROI of at least 50 (5,000%) times the initial investment while a further 28% saw an ROI of 10 to 49 times the investment. The median company return is 700% indicating that typically a company can expect a return of 7 times the initial investment” (PWC/ICF (International Coaching Federation) Global Coaching Study, 2009).

“How much am I/the value I bring worth?” is subjective and may depend on the coach’s confidence in themselves – too much and a coach may inflate their fee inappropriately; too little and they may be selling their services cheap. But if we were to use a value pricing model, might we charge 700% of our costs and time to match the 700% ROI noted above?

A simpler way might be to look at the Return on Expectations, where the client approximates the perceived value of the service provided. This might take us to some interesting pricing discussions around time saved, operational efficiencies made, value added.

It’s easy to see why we are struggling to clarify fee rates in our coaching community. We’re not saying every coach needs a matrix of 50 + price points, but we do need to identify our target market and price accordingly. Our argument is that despite this being an unregulated market, it would be incredibly useful to coaches if there were some benchmark figures against which to set their pricing strategy. As we identified earlier in this article, there are at least nine variables that would need to be accounted for. To manage this complexity, we would need to involve organisations who understand how to simplify the vagaries of compensation.

We would like to encourage the coaching bodies to embark on such a benchmarking study. Before we get to that point though, we will look at the variables for team coaching in the next article in this series.

- Contact us

- Michelle Lucas: michelle@greenfieldsconsultancy.co.uk

- Clare Norman: clare@clarenormancoachingassociates.com

- Next issue: team coaching variables

References

- Association for Coaching, UK Coaching Rates 2004

- C Mann, 6th Ridler Report, London: Ridler & Co, 2016

- G Olivero, D Bane and R Kopelman, “Executive coaching as a transfer of training tool”, in Public Personnel Management, 26(4), 1997

- Bersin & Associates, High-Impact Performance Management: Part 1 – Designing a Strategy for Effectiveness, 2011

- P S Wise and L S Voss, The Case for Executive Coaching, Lore Research Institute, 2002

- PWC/International Coaching Federation, Global Coaching Study, 2009

Table 1: Setting up a coaching business – Costs to consider*